Turning the Tide

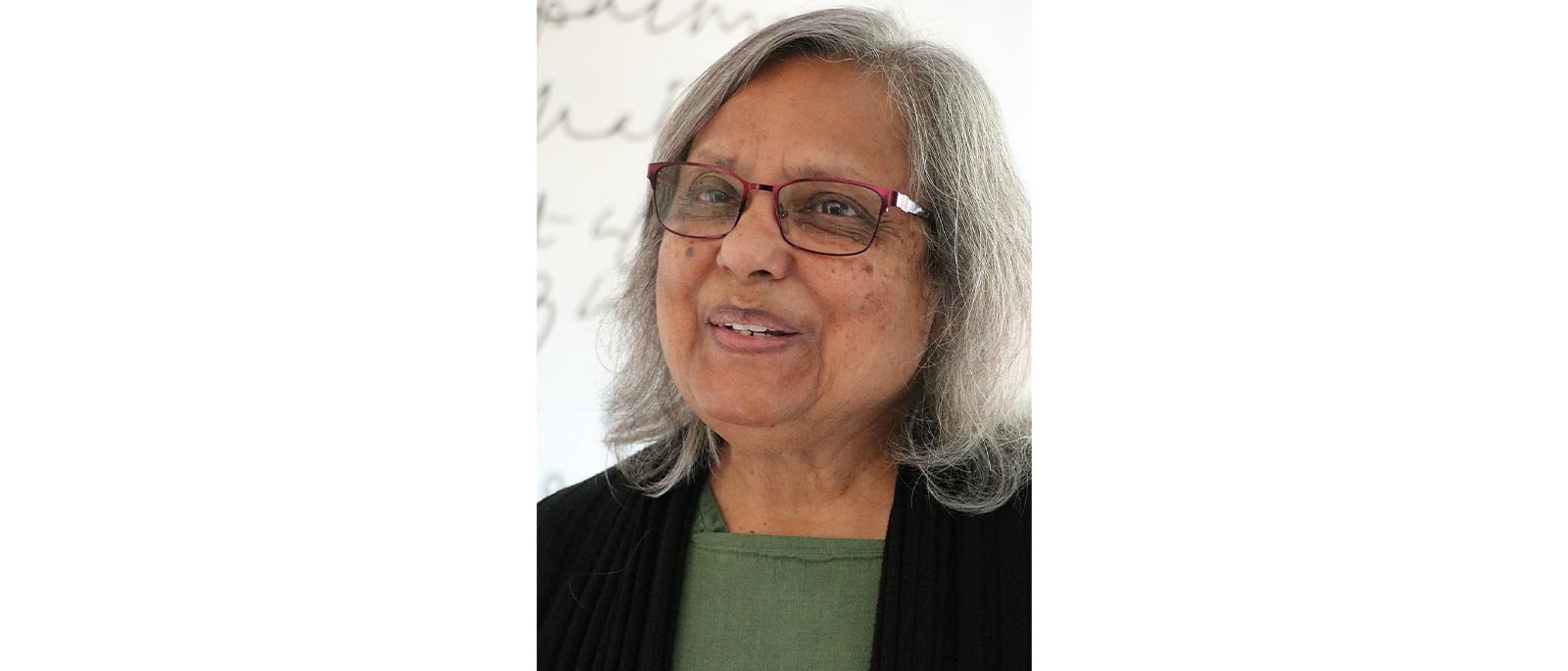

Before the Met-premiere of Philip Glass’s Satyagraha, Ela Gandhi spoke about the idea of satyagraha and her grandfather’s incredible legacy.

Philip Glass’s opera Satyagraha, which has its Met premiere in 2008 and returned three years later, was inspired by Gandhi’s early years in South Africa, where he developed his philosophy of non-violence. On the eve of the premiere, his granddaughter Ela Gandhi spoke about his legacy, her own youth in South Africa, and her family’s work on Indian Opinion, the newspaper founded by Gandhi. She refers to her grandfather as “Gandhiji,” using the Indian form of address that is both affectionate and respectful.

“Satyagraha” is translated as “force of truth.” How did the term come into being?

Gandhiji did not like the word “passive resistance” for a movement that was far from passive, so he asked people to submit possible names, and from this the word satyagraha emerged. It really describes Gandhiji’s philosophy. Truth as a holistic concept takes into account socio-economic issues, political and religious issues, and the need for respect among people, regardless of race, ethnicity, or religious or gender considerations.

How do you live your life according to its terms?

There is need for strict discipline and control over one’s emotions and urges. This comes from a way of life which is simple, respectful, compassionate, enjoyable, and yet not lavish, which is considerate of others and responsive to the needs of others, and which is actively engaged in trying to bring about the kind of changes necessary so everyone can live a good life and has access to its basic necessities.

Do you think an opera about satyagraha can educate and enlighten?

Music, opera, drama, and other forms of art convey feelings and reflect the times. While words can express things openly and in a way that people can easily understand, the arts express the same things in a more subtle way. Over the years many great poets, musicians, and dancers all expressed their feelings about societal issues and it made an impact on the community.

Tell us about Indian Opinion, the newspaper your grandfather started.

The newspaper became the center of our lives. We had to set each alphabet by hand, write addresses by hand and cut, fold, and wrap by hand. This took the entire week. The paper was a vehicle to educate the community on what was happening and on the political issues of concern to them. It helped in raising issues of racism. My father also exposed the harsh prison conditions after having been imprisoned, which contributed to the gradual improvements in the condition of prisons.

You spent your youth in the Phoenix Settlement near Durban in South Africa.

We originally lived in a little wood-and-iron building that was on the land when Gandhiji purchased it in 1904. By the time I was five the building was falling apart and my father decided to build a blockhouse. We made the blocks ourselves, it took almost a year to put up the building. Phoenix Settlement was a unique place in apartheid South Africa, since we were growing up with people of different race groups. We learnt a lot about farming and all kinds of work, and about the dignity of work.

What else did these years teach you?

It was a life lesson. I learned to appreciate the value of simplicity, not hankering after fashion and all the consumerism that we see today. We were satisfied playing with used cans and a ball, or a piece of wood to serve as a bat. We had no radio or TV for many years, and did not miss it. My greatest lesson was how happy one can be with so little.

How do you remember your grandfather?

I remember staying with him some months prior to Indian independence [in 1947]. I had a set time when I and other children in the ashram could gather around him and talk, tell stories and play with him. These were some of the most precious memories. He gave us undivided attention at such times. Being a child I did not realize my grandfather’s stature. To me he was my grandfather.

In spite of Gandhi’s teachings, the world has become a more violent place since his death.

Certainly the past century and the beginning of this have seen an increase both in violence and in cruelty. Humankind has not learned from the lessons of the holocaust. There’s still fervor for power to preserve things at any expense and for the Nazi notion of “ethnic cleansing,” which is cruel, debasing and inhuman to a degree beyond imagination. Remorse and resistance against such acts are lacking with the result that the perpetrators defend their acts and try to shoot down the critics.

It’s now 60 years since Gandhi’s assassination. What is his enduring legacy?

Fortunately there is an overwhelmingly large majority of people who want change, and they see the absolute relevance of Gandhian ideas. They are trying their best to turn the tide. Humankind can sit back and say that we have lost. But we cannot take the challenge and begin the process of bringing about change if we don’t do it in ourselves first and then in others. As Gandhiji said: “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.”