Scientific Inquiry

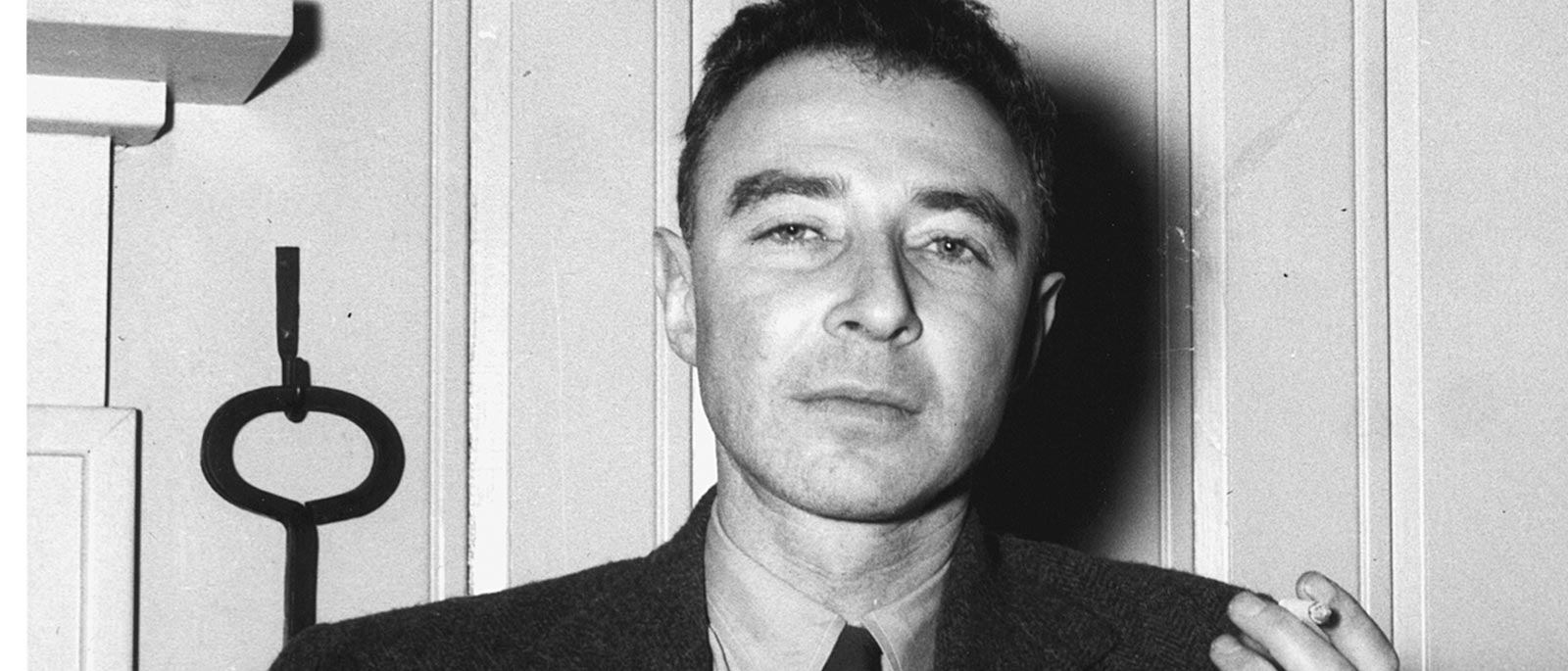

Learn about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the brilliant Manhattan Project physicist at the center of John Adams’s Doctor Atomic. By Caroline Cooper

The head of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos test site, J. Robert Oppenheimer was widely known for his voracious intellect, his crisp martinis, the cigarette forever locked between his index and middle fingers, his interest in Eastern philosophy, and his entanglements with a U.S. government that came to suspect him of communist sympathies. Known as the “father of the atomic bomb,” the physicist led a life at the forefront of science, working at a pace few could sustain. As he described himself to the Berkeley police following an ill-begotten evening out, “I am eccentric.”

Oppenheimer’s interest in science started in childhood, as he parsed through a mineral collection his grandfather gave him, developing what Oppenheimer termed “a fascination with crystals, their structure.” The son of Julius Oppenheimer, a well-to-do textile importer, and Ella Friedman, a Baltimore artist, young Robert grew up comfortably in New York. (The family’s private art collection featured three Van Goghs.) In 1922 he enrolled at Harvard University, graduating summa cum laude in three years.

As a graduate student at Cambridge, Oppenheimer encountered quantum theory, the strain of science that would capture his imagination. But he struggled under the weight of his interests and at Cambridge was wrongly diagnosed with schizophrenia by a Harley Street psychiatrist. He left the school and went to the Georg-August-Universität in Göttingen, Germany, where he received his doctorate in 1927. Two years later, he was back in the U.S., on the faculties of Cal Tech and the University of California at Berkeley. He remained at both institutions until 1947.

Oppenheimer’s advancements in the field of theoretical physics included new insights on the quantum behavior of molecules, and his research laid the groundwork for understanding black holes, relativistic quantum mechanics, quantum field theory, and cosmic rays.

His achievements attracted the attention of the U.S. military in its efforts to develop atomic weaponry. General Leslie Groves, the military officer in charge of the Manhattan Project, chose Oppenheimer to lead the expansive Los Alamos test site. To execute the demands of the project, which delivered the bomb in just over two years and cost more than $2 billion, Oppenheimer gathered nearly 4,000 of the best minds in science to Los Alamos, which he dubbed “Trinity,” a reference to a John Donne poem.

At precisely 5:30AM on July 16, 1945, the horizon of the New Mexico desert flashed white with what historian Richard Rhodes has termed “a dawn coming from the entirely wrong direction.” As has often been reported, Oppenheimer watched the explosion unfold with a passage from the Bhagavad Gita, the Hindu sacred epic, on his lips. “I am become Death,” he said, “the shatterer of worlds.” Reflecting on that momentous occasion, he later stated, “We knew the world would not be the same.”

But the political implications of the bomb and its use by the U.S. and other governments were topics Oppenheimer felt best left to others. “Scientists are not delinquents,” Oppenheimer said in a 1961 interview. “Our work has changed the conditions in which men live, but the use made of these changes is the problem of governments, not of scientists.”

Still, Oppenheimer expressed reluctance about Truman’s use of the bomb against Japan and lobbied in later years against the development of the even more powerful hydrogen bomb. The country, however, celebrated Oppenheimer and his team for their work, spiriting the bomb off immediately for use against Japan and awarding him a Presidential Citation and a Medal of Merit.

Over time, the physicist came to recognize the profound impact his creation has had on global affairs. “The atomic bomb was the turn of the screw,” Oppenheimer said during this period. “It has made the prospect of future war unendurable. It has led us up those last few steps to the mountain pass; and beyond there is a different country.’’

Oppenheimer’s prestige came crashing down in a tide of communist suspicions that led President Dwight D. Eisenhower to call for a “blank wall to be placed between Dr. Oppenheimer and any secret data” pending a security hearing in 1954. His security clearance was never restored, though he would know some retribution when, in 1963, he was awarded the prestigious Fermi Award, the U.S. government’s lifetime achievement award for the development and study of energy, four years before succumbing to throat cancer at his home in Princeton, New Jersey.